Liner notes for Mads Tolling,

Celebrating Jean-Luc Ponty

Liner notes for Mads Tolling,

Celebrating Jean-Luc Ponty

Re-crossing the Enigmatic, Generational Ocean

A strong sense of poetic logic, not to mention cross-generational and transatlantic resonates on Mads Tolling’s robust and subtle “neo-fusion” tribute to his hero Jean-Luc Ponty. Both musicians are violinists blessed with both virtuosity and melodic grace, and with a passionate, umbilical link to jazz of different eras and attitudes. For these artists, the term “fusion” is a way of being rather than restrictive genre garb. Both have also easily moved from their European roots – Ponty from France, Tolling from Denmark – and matriculated smoothly onto American soil, and enriched the universal language of jazz.

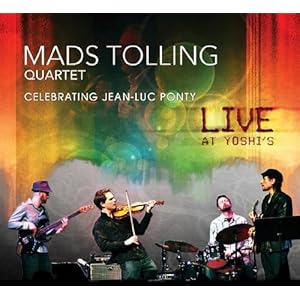

Add to these attributes the fact that Tolling found his career and musical life path steered by Ponty himself, who introduced the young, gifted Dane to Ponty’s sometime colleague Stanley Clarke, in whose band Tolling was a vibrant member for several years, and the sense of rightness and circularity synch up with the power of the musical end result itself. Joined by his dazzling and tightly integrated San Francisco-based band, with the dynamic, nimble guitarist Mike Abraham, bassist George Ban-Weiss and drummer Eric Garland, Tolling puts forth a vibrant, present-tense sound which is also steeped in the ‘70s fusion era, in the most artful sense of that sometimes dubious genre. Fusion is alive, well, and revitalized in the hands of artists like Tolling.

Recorded live in the famed jazz room, Yoshi’s, in Oakland, California, the music here has a warmth and intensity somehow amplified by the in-the-moment liveness of the occasion. The fiery moments are fierier and the tender moments more moving, in the real time context. Implicitly, a thematic focus has to do with the symbiotic relationship of a very now proposition from these ‘00s with a respectful consideration of musical values and substance going back to the ‘70s and beyond, with Ponty always in the contextual crosshairs.

Tolling explains that “I think it was my goal with this album to have a

wide range material that was closely related to (Ponty) – I didn’t want to

recreate his compositions, but give a new take on them and also show the great

range of projects he has done through the years, including Zappa’s band,

Mahavishnu Orchestra, Rite of Strings, the swing and bebop he did early on,

hence `Old Country,’” he says, referring to the Cannonball Adderley composition

on the program.

“To me, `Beatrice’ (the Sam Rivers-penned ballad) shows a side of what he

stands for as well, which is a conservatory- trained violinist playing jazz, and

integrating sounds from the classical violin technique, as well as rock and jazz

elements. It has always been my goal to show the violin in a multi-genre,

multi-faceted way.”

In general, Tolling has approached this Ponty project as a means of

“creating a portrait of his music making through the years, while paying

tribute. I think a key part was also to write for the Mads Tolling Quartet, so a

lot lies in the arrangements and the players.”

Fittingly for a Ponty tribute according to Tolling, the violinist-bandleader moves laterally across a varied landscape of relevant material, with the requisite taut unison lines, sophisticated harmonic changes and rhythmic tides of swing, rock and balladic sway along the way. Tolling’s own ambitious pocket-sized epic of a tribute, “Ponytfication,” plays like a letter from protégé to mentor, using some of the mentor’s vocabulary but actually demonstrating the student’s own assured creative insights. A grand, suite-like Ponty medley of mostly Ponty tunes, including “Enigmatic Ocean” and the framing devices of the intro and outro to “Struggle of the Turtle to the Sea,” as well as his old ally Frank Zappa’s “King Kong” in the mix. Ponty’s way with a ballad is duly honored with the band’s softly glowing take on “Last Memories of Her,” with Tolling on the tonally-expanded octave violin.

Over the course of the carefully-chosen musical program, the musical panorama widens, as it should, to fully tell the tale of Ponty’s musical life so far. Things open hypnotically and with a snort of musical adrenaline with the restless meditations and metric new math of John McLaughlin’s “Lila’s Dance” and the proto-fusion lineage continues with Clarke’s classic ‘70s tune “Song to John,” in homage to John Coltrane, and revisited in the version Tolling has devised for his own quartet (he has also arranged this piece for the “other” primary group he plays in, the acclaimed and jazz-fluent Turtle Island String Quartet).

On the album, Tolling also bridges jazz generations by including versions of both Ponty’s “New Country” and Adderley’s “Old Country.” The pair was chosen for much more than the similarity of titles. As Tolling explains, “one is what sounds like to me is Ponty's optimistic outlook on life after moving to USA and doing quite well, making a sort of a joyous fiddle song. That contrasts with `Old Country,’ which implies a melancholic story to it of a man sitting on the side of the road with a life of opportunities passing him by.”

Tolling demonstrates his powers of self-generative musical expression

with the bittersweet radiance of his solo version of Rivers’ lovely, ruminative

ballad “Beatrice,” written for Rivers’ wife. “Actually,” Tolling comments. “I

was aware of how beautiful the piece was for a while, but when I really started

thinking about it was when one of my students were over, and he told me that he

had been playing it in his jazz combo. It interested me for one because the

melody as a solo sounds almost like a war song without the harmony – simple, and

then as an arrangement starting to incorporate the harmonic progression. The

tune has a natural way that it can progress.”

As much as Tolling’s current project pays due respect to a pioneering

forerunner of the instrumental and stylistic field the Dane is heavily invested

in, this powerful music is also a statement of ensemble prowess by a group

deserving kudos in the realm of next generation fusion.

But what’s in a name? Concerning the matter of categories and musical

tags by which this music might be identified, Tolling concedes that “some people

would call this `old fusion,’ but for me it’s about playing that music in the 21st

century with the players and sensibilities that are around now. Somehow after

the ‘80s, the fusion name and sound somewhat went out of style. I guess I can

see why as it had run its course, and some of the sounds and looks of it could

be called corny and dated. Part of it is that it was never hip listening to your

parents’ music, so something more acoustic took its place.

“I do feel that fusion is due for a revival. It has a lot of energy and

as things move in cycles, it seems as though it could happen. I do think it

involves a different taste now than in the ‘70s, and as a new artist, I am

trying to weave the now and the past together in a way that makes sense. I feel

it’s great music, and the violin played quote the role in the fusion days – the

violin was accepted – whereas if you walk to a traditional jazz jam session,

people might look a little funny.”

We can count Tolling as part of the new breed of technically adroit and, even more importantly, conscientiously musical violinists who are making the violin once more accepted into the ranks of the jazz world. Just as Ponty declared a new era and level of artistry starting four-plus decades back, Tolling is on the case, for artistic evolution’s sake.

--Josef Woodard, contributor to Down Beat, Jazz Times, Jazziz, Los Angeles Times, and other publications. He wrote the book The Montgomery Brothers: Wes, Buddy and Monk, and is currently finishing a biography of Charles Lloyd.